#002 Forest Fires

Climate Risks & Carbon Sinks Newsletter

By Ajay Goyal, Founder & CEO @ ForestSAT.space

Biggest Wildfires in History:

Top 12 Largest Wildfires in History

1. 2003 Siberian Taiga Fires (Russia) – 55 Million Acres

2. 1919/2020 Australian Bushfires (Australia) – 42 Million Acres

3. 2014 Northwest Territories Fires (Canada) – 8.5 Million Acres

4. 2004 Alaska Fire Season (US) – 6.6 Million Acres

5. 1939 Black Friday Bushfire (Australia) – 5 Million Acres

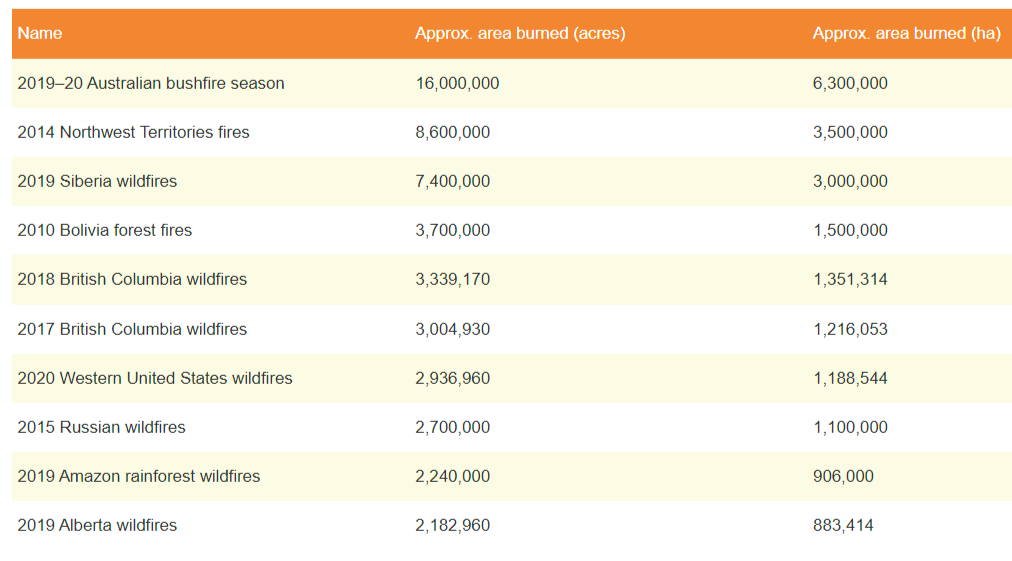

Biggest wildfires of the decade:

Primer on Wildfires:

A wildfire, forest fire, bushfire, wildland fire or rural fire is an unplanned, uncontrolled and unpredictable fire in an area of combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identified as a bushfire(in Australia), desert fire, grass fire, hill fire, peat fire, prairie fire, vegetation fire, or veld fire.

Forest Fire Challenge

- Fires are now causing an additional 3 million hectares (7.4 million acres) of tree cover loss per year than they did in 2001, according to a newly released Global Forest Watch analysis that examined fires that burn all or most of a forest’s living overstory trees.

- The majority of all fire-caused tree cover loss in the past 20 years (nearly 70%) occurred in boreal regions. Although fires are naturally occurring there, they are now increasing at an annual rate of 3% and burning with greater frequency and severity and over larger areas than historically recorded.

- Fires are not naturally occurring in tropical rainforests, but in recent years, as deforestation and climate change have degraded and dried out intact forests, fires have been escaping into standing tropical rainforests. GFW findings suggest fires in the tropics have increased by roughly 5% per year since 2001.

Wildfires: How They Form, And Why They’re So Dangerous

There are three conditions that must be present in order for a wildfire to burn. Firefighters refer to it as the fire triangle: fuel, oxygen, and a heat source. Four out of five wildfires are started by people, but dry weather, drought, and strong winds can create a recipe for the perfect disaster—which can transform a spark into a weeks- or months-long blaze that consumes tens of thousands of acres.

Across Russia, Europe, Indonesia, the Amazon Basin, North America, Australia, and beyond, we have watched fires blaze across landscapes, causing immense damage to life and land. Now, a new analysis confirms what many have witnessed firsthand and in the news: forest fires are getting worse.

Resources

Forest Fires- wildlifesos.org

CIFOR’s focus – Forest Fire

Causes and effects of global forest fires – WWF

Wildfires and Climate Change – western United States.

Wildfires are becoming more common in the UK – but the threat can be managed theconversation.com

Additional wildfires break out in Europe as extreme heat continues- Wildfiretoday

News & Reports

Wildfires are becoming more dangerous – here’s why- Wildfire in Greece

Forest fires have burned a record 700,000 hectares in the EU this year- euronews.com

Wildfires: A Crisis Raging Out Of Control? WWF

Wildfire damages cost €2 billion last year, says EU Commissioner euronews

Climate change: Europe and polar regions bear brunt of warming in 2022 bbc.com

Europe’s ‘pyroregions’: Summer 2022 saw 20-year freak fires in regions that are historically immune phys.org

Wildfires destroy twice the forest cover today compared to 2 decades ago: 9.3 million hectares of tree cover was lost globally in 2021

New Data Confirms: Forest Fires Are Getting Worse www.preventionweb.net

Climate change driving unprecedented forest fire loss euractiv.com

Forest fire hits northern Germany’s highest peak Hundreds of tourists were evacuated after thick smoke engulfed an area south of the summit of the Brocken mountain. Located in the Harz National Park, the area has seen several wildfires this year. Dw.com

Extreme wildfires pollute the air people breathe; Drought and heat waves are fueling a widening global fire front that is choking the air we breathe. www.dw.com

Europe set for record wildfire land loss in 2022 : Nearly 660,000 hectares of European land have already been destroyed by fires this year. www.dw.com

Bodies and Organization

UN Food and Agri Forests Organization fao.org/forests

US Forest Services fs.usda.gov

Australia Forestry agriculture.gov.au

Canadian Forestry Department nrcan.gov.ca

European ForestB institute https://efi.int/

Indian Forest Service ifs.nic.in/

European Forest Fire Information System EFFIS

Calfire fire.ca.gov

World Health Organization WHO

Forest Fire SOS in India – Wildlife SOS

Wildfire Investigations-U.S. Department of the Interior

Forest fires and climate change- Forestresearch

Wildland Fire USDA

Global Forest Watch Global Forest Watch, an environmental monitoring platform developed by the World Resources Institute

Reports

Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires: A new report, Spreading like Wildfire: The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires, by UNEP and GRID-Arendal, finds that climate change and land-use change are making wildfires worse and anticipates a global increase of extreme fires even in areas previously unaffected. Uncontrollable and extreme wildfires can be devastating to people, biodiversity and ecosystems. They also exacerbate climate change, contributing significant greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere. unep.org

European Forest Fire report: Three of the worst fire seasons on record took place in the last six years europa.eu

European Commission Annual Report on Forest Fires in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa in 2021. It concludes that last year’s fire season was the second worst in the EU territory in terms of burnt area (since records began in 2006), after 2017 when over 10,000 km² had burnt. More than 5,500 km² of land burnt in 2021 – more than twice the size of Luxembourg – with over 1,000 km² burnt within protected Natura 2000 areas, the EU’s reservoir of biodiversity. jrc.ec.europa.eu

Indicators

Climate Change Indicators: Wildfires This indicator tracks the frequency, extent, and severity of wildfires in the United States.

https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-wildfires

Carbon dioxide and other emissions from fires

Over the past century, wildfires have accounted for 20-25% of global carbon emissions, the remainder from human activities.Global carbon emissions from wildfires through August 2020 equaled the average annual emissions of the European Union.In 2020, the carbon released by California’s wildfires were significantly larger than the state’s other carbon emissions.

Wildfires release large amounts of carbon dioxide, black and brown carbon particles, and ozone precursors such as volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides (NOx) into the atmosphere.

What is causing California Wildfires

a confluence of factors has driven the surge of large, destructive fires in California: unusual drought and heat exacerbated by climate change, overgrown forests caused by decades of fire suppression, and rapid population growth along the edges of forests.

Eight of the state’s ten largest fires on record—and twelve of the top twenty—have happened within the past five years, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire). Together, those twelve fires have burned about 4 percent of California’s total area—a Connecticut-sized amount of land.

Two recent incidents—the Dixie fire (2021, above) and the August fire complex (2020)—stand out for their size. Each of these burned nearly 1 million acres—an area larger than Rhode Island—as they raged for months in forests in Northern California. Several other large fires, as well as many smaller ones in densely populated areas, have proven catastrophic in terms of structures destroyed and lives lost. Thirteen of California’s twenty most destructive wildfires have occurred in the past five years; they collectively destroyed 40,000 homes, businesses, and pieces of infrastructure.

The total area burned by fires each year and the average size of fires is up as well, according to Keith Weber, a remote sensing ecologist at Idaho State University and the principal investigator of the Historic Fires Database, a project of NASA’s Earth Science Applied Sciences program. The database shows that about 3 percent of the state’s land surfaces burned between 1970-1980; from 2010-2020 it was 11 percent. The shift toward larger fires is clear in the decadal maps (above) of fire perimeter data from the National Interagency Fire Center.

The effects of all these fires are dramatic from the ground and from space. The false-color image at the top of the page, captured by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, shows the burn scar left by the Dixie fire. The blaze destroyed 1,329 structures and cost hundreds of millions of dollars to fight. The photograph below shows charred forests in Plumas National Forest in the wake of the Dixie fire.

Impacts of disasters leading to forest fires

UNFF16-Bkgd-paper-disasters-forest-fires

- Deforestation: the long-term or permanent conversion of forest to other land uses, such as agriculture, pasture, water reservoirs, infrastructure and urban areas. Deforestation is responsible for one-fifth of total GHG emissions globally; it also has detrimental impacts on other natural resources such as water and biodiversity, as well as on local livelihoods and national economies

- Degradation: the reduction of the capacity of a forest to provide goods and services. This can be caused by a natural or a man-made disturbance, or a product of the two. Absence of corrective measures countering degradation can lead to total and perpetual loss of goods and services provided by forested lands

- Disturbance: an event or force, of nonbiological or biological origin, that brings about mortality to organisms and changes in their spatial patterning in the ecosystems they inhabit. Disturbance plays a significant role in shaping the structure of individual populations and the character of whole ecosystems. It is often characterised by its intensity, its frequency, its size, and its scale, among other aspects

- Drought: complex phenomena triggered by the absence of water over a long period of time, which can adversely impact vegetation, animals and people. Meteorological droughts happen when precipitation is insufficient; hydrological drought refers to the low amount of water in a hydrological system; agricultural drought refers to crop damages linked to long-term water shortages; and socioeconomic drought refers to the shortage of commodities due to drought

- Pest: any organism (e.g., fungi, insect, virus) occurring in unsustainable numbers that can threaten the health and vigour of a forest, its biodiversity, and the many social, cultural and economic goods François-Nicolas Robinne UNFFS Background paper 7 and services it provides. Pests can be native, with natural outbreaks occurring periodically; they can also be alien when introduced from outside of a given ecosystem. Both native and alien pests can become invasive when they extend beyond their known usual range, due for instance to climate change

- Windthrow: uprooting and steam breakage caused by wind, which often leads to trees’ death. This common forest disturbance can range from a windfall affecting a small tree stand to an entire forest blown down during extreme weather events such as cyclones

Decades of fire suppression fuel catastrophic wildfires today

A single event in American history led to a century-old, failed government policy that delivered the primary cause of today’s crisis—too much wood in the woods.

Fuel loads today are so dense and forests so radically altered that it is nearly impossible for there to be anything resembling a “natural” fire. Forest scientists studying the drivers of high-severity fire in the West have found that the fuel loads in our forests are by far the most important factor, followed far behind by fire weather, climate, and topography. Today, 63 million acres, or one-third of the land in our national forests—an area the size of Oregon—are at high risk of catastrophic wildfire.

Fire suppression fueled California’s destructive 2020 blazes, study says latimes.com

Before colonization, though, such wildfires helped keep the state’s vast forests healthy by burning underbrush and triggering trees to release their seeds, according to scientists.

The 2020 wildfires marked a turning point. Fires burned 4.2% of the state that year, about the acreage annually consumed by fire before European and American settlement.

A century of fire suppression has left California with what the researchers call a “massive fire deficit” as forests become choked with trees and undergrowth.

The payback in 2020 was devastating. All that fuel, rising temperatures, drought and high winds dramatically increased the intensity and speed of wildfires, which burned 2.2 times more land than the previous record set only two years earlier.

Catastrophic effects of Wildfires

- Wildfires and volcanic activities affected 6.2 million people between 1998-2017 with 2400 attributable deaths worldwide from suffocation, injuries, and burns, but the size and frequency of wildfires are growing due to climate change.

- Resulting air pollution can cause a range of health issues, including respiratory and cardiovascular problems.

- Another significant health effect of wildfires is on mental health and psychosocial well-being.

Wildfires or forest fires can have significant impact on mortality and morbidity depending on the size, speed and proximity to the fire, and whether the population has advanced warning to evacuate.

Wildfire smoke is a mixture of air pollutants of which particulate matter is the principal public health threat.

Infants, young child, women who are pregnant, and older adults are more susceptible to health impacts from smoke and ash, which are important air pollutants. Smoke and ash from wildfires can greatly impact those with pre-existing respiratory diseases or heart disease. Firefighters and emergency response workers are also greatly impacted by injuries, burns and smoke inhalation.

Wildfires also release significant amounts of mercury into the air, which can lead to impairment of speech, hearing and walking, muscle weakness and vision problems for people of all ages.

Wildfires and Climate Change

Climate change has been a key factor in increasing the risk and extent of wildfires in the Western United States. Wildfire risk depends on a number of factors, including temperature, soil moisture, and the presence of trees, shrubs, and other potential fuel. All these factors have strong direct or indirect ties to climate variability and climate change. Climate change enhances the drying of organic matter in forests (the material that burns and spreads wildfire), and has doubled the number of large fires between 1984 and 2015 in the western United States.

Research shows that changes in climate create warmer, drier conditions. Increased drought, and a longer fire season are boosting these increases in wildfire risk. For much of the U.S. West, projections show that an average annual 1 degree C temperature increase would increase the median burned area per year as much as 600 percent in some types of forests. In the Southeastern United States modeling suggests increased fire risk and a longer fire season, with at least a 30 percent increase from 2011 in the area burned by lightning-ignited wildfire by 2060.

The science connecting wildfires to climate change

A heating-up planet has driven huge increases in wildfire area burned over the past few decades.

The clearest connection is with warming air temperatures. The planet has heated up nearly continuously since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1800s, when humans started burning massive quantities of fossil fuels, releasing carbon dioxide that traps excess heat in the atmosphere. Since then, global average temperatures have ticked up roughly 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius); California’s change is closer to 3 degrees Fahrenheit. Warming has accelerated since the 1980s to just under 0.2 degrees Celsius (0.3 degrees F) per decade, and it’s likely to accelerate further in the future.

A particularly severe phase of that persistent drought, fueled by climate change and of an intensity not seen for the preceding 1,200 years, set in between 2012 to 2016. It stressed out the region’s trees more and more as the water deficit dragged on. In the grand conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada, as in many other forests across the state, the damage accumulated.

By 2014, millions of trees had died, pushed beyond repair by the record-breaking temperatures and dryness, which reached so far into the soil that even the deep-rooted trees could find no moisture. By 2015, mass die-off was obviously underway; by 2016, the mortality count soared to about 100 million. At high elevations, nearly 80 percent of the trees died. And across the state, some 150 million trees have died since the drought’s onset. Many of those trees are still there, drying out, a major fuel source ready to burn hot and bright when a fire arrives.

++ The End ++